We’re All Risk Managers Now

- bilal486

- Jul 30, 2025

- 11 min read

By David Gray, Sales and Growth Lead, Phlo Systems Ltd

‘In fifty years or so,

It’s gonna change, you know,

But it’s perfect nowadays’Nowadays’

(Chicago the Musical) 1975

Art, they say, imitates life. Or maybe it’s the other way around. Either way, here we are. It is 50 years, exactly, since those lyrics were written.

There was a time when we were told that there were two taboo dinner party conversation topics: sex and religion. Politics is earning its place as a third taboo. But it has also become clear that there is a massive by-product of politics that is changing the way we need to look at the world.

With a nod to Lionel Shriver, we need to talk about risk. Broadly, there are multiple types of risk that investors focus on, such as political risk, credit risk, price risk, environmental risk (including access to water) and so on. Despite war, erosion of political buffers and wholesale interference in the broad free trade model enshrined in the Global Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) signed in 1947, and the creation of the World Trade Organization in 1995, markets seem to be discounting these risks and risk premia are vanishing. But risks crystallize in two general ways: some are immediately apparent, with a range of knowns and unknowns, and those which develop, almost stealthily, over time. Daily news headlines announce policies or developments which commentators say fuel uncertainty, which investors tend to find unwelcome, but market indices trend up. Consequently, what seems to be happening is something of a confluence where we see quite striking examples of both kinds of risk happening at scale simultaneously.

For commodities, and in particular agricultural commodities, it has always been the case that markets are directly impacted by uncontrollable externalities: weather, access to water, macroeconomic factors, government policies (including regulation), changing consumer preferences to name a few. Over the past 50 years, food security has been inextricably connected with free trade: the relative certainty that food importing countries could count on to access global tradeable surplus across world markets, characterized by reliable logistics, transparency of pricing and active market-makers. Absent crisis, such as droughts, governments have tended to avoid interfering in markets either because they did not want to restrict domestic producers’ access or because they needed certainty of supply; data show that farmers whose access to world markets is impaired achieve lower prices and worse financial outcomes than their free-trading counterparts. More broadly, as has been widely reported and is being experienced today, globally diversified and integrated supply chains can be upended and substantial value disrupted by unilateral government action.

In a sense, farmers are fortunate among producers of commodities. Forecast global population growth and demand for calories can mitigate many potential challenges arising from cyclical demand variations or macroeconomic variables that are inherent in most other commodity types. This aggregation of factors has long been the foundational premise for institutional investment in agriculture, and a core value attribute for farmland as an asset class.

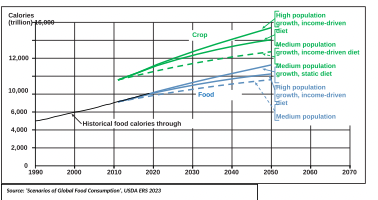

FORECAST AVAILABLE CROP AND FOOD CALORIES 2011-2050

There is, inevitably, a loss of caloric value as crops get converted to food. Crop calories, though, are also a proxy for pressure on land use or plantable acreage. As a reference, under the Medium Population Growth scenario world agriculture production would have to increase to over 14 trillion calories (approximately 15%) to feed a global population of 9.7 billion people by 2050. Demand for food also reflects income levels: higher incomes drive increased calorie consumption. This has also been central to the thesis for investor interest in agriculture: with rising food prices should come higher land values, accentuating farmland’s profile as an investment that is both defensive and inflation-hedged.

Of course, this view still resonates but it is by no means a certainty. Decoupling land value from underlying economic performance is dangerous. Higher interest rates create an arbitrage between levels of cash return generally assumed as part of any investment profile and US Treasuries with comparable yields that would represent the risk-free rate in a DCF. Wizened investors would be forgiven for asking, in view of past and even ongoing debates about the level of the debt ceiling in the US and the spectre of potential default, whether ‘risk-free’ is, really, risk-free. With the recent Moodys downgrade of US credit risk from AAA to Aa11, there are 9 other countries whose unanimous AAA credit risk profile is now deemed superior to that of the US2. Fifty years ago, this was unthinkable.

Enter the frog

Back in 1975, US farmers were able to generate positive returns from growing the nine principal cash crops before any contribution from farm safety net programs. For the 46 years between 1975 and 2020, so-called safety net payments turned a -7% market net return into a +4% profit3. The level of reliance on outside support has, almost imperceptibly, increased dramatically over time and this has some far-reaching and impactful consequences for growers and investors alike.

Compounding this trend, we would argue that recent US policy and government interventions have only increased the importance of ‘support’ payments to overall farm economy well-being. More broadly, it seems irrefutable that the balance of power in agriculture is shifting irreversibly, and that this will have – is having – a visible impact on key trade flows. The most obvious example of this is soy purchases by China. The past 8-9 years have seen a structural shift exports of soybeans to China, with the US the net loser in the battle with Brazil.

Two factors emerge from the table above. First is the structural nature of the shift in exports that has taken place since 2017. The second is that, broadly speaking, US soy exports to China, in bushels, have stagnated, while Brazilian exports have almost doubled since 2016. Put another way, all the growth in Chinese consumption has been provided by other countries (or increased domestic production) but is another indicator of the extent to which US government intervention in markets has disadvantaged domestic growers.

Over the same period, direct government payments by the USDA and other US government departments, excluding emergency/ad hoc assistance during Covid, including forecast payments for the 2025 crop year, exceed $211 billion.4 Average annual disaster/emergency support payments between 2016-2019 were $925 million; between 2020-2024 they reached an annual average of over $18 billion. While some of this is attributable to the pandemic when levels of government support across the economy were elevated globally, looking just at the post-pandemic years of 2023-2024, supplemental/ad hoc support totalled $11.4 billion, or an average of $5.7 billion annually. In 2025, USDA estimates show this skyrocketing to about $35.7 billion.5

It can be argued that payments on this scale represent a large and likely unsustainable transfer of risk from farmers to taxpayers as a group. Since the value of direct farm payments is often capitalized into land value, this distorts its value; effectively the direct payments are treated as ordinary income and thus part of annual profit calculations. The challenge is that these payments are in effect subsidies that are based on need, so the antithesis of ordinary income. Further, it can be argued that subsidies of this sort artificially reduce risk: in 2023 the Cato Institute reported that, ‘In recent years, the annual rate [of bankruptcies] has averaged 2 per 10,000 for farm businesses compared to between 4 and 7 per 10,000 for all U.S. businesses’.6 That this has happened over a number of years means that we have been less aware of the increasingly ‘locked in’ or ‘normalized’ nature of assumed or required government support. This is the water heating up around the frog.

Contrast

Some risks crystallize quickly – outcomes that are broadly predictable based on facts or changes in policy. From a US perspective, we are now experiencing a succession of policy announcements related to the imposition of tariffs, followed by retaliation, then amendments, deferrals and increases in scope that are happening at the economic equivalent of warp speed. ‘Trade deals’ are being sought, announced and even subject to negotiations that are ‘terminated’. We are frequently told that, despite numerous statements of intent, severity of the tariffs was somehow unexpected. Now they have been imposed – or are threatened to be imposed at unprecedented levels – and anxiety has increased about their impact on the US and world economy. Central banks and other forecasters have pretty unanimously lowered the outlook for global growth as a result. Away from tariffs, on July 8, 2025 the Trump administration announced that it would move to prevent purchases of US farmland by Chinese and other foreign interests on national security grounds. About 4% of US farmland is owned by foreign interests, mostly from Europe and Canada, which owns about 1/3 of all US farmland owned by foreigners.7 What this could mean in terms of competition to purchase land is unclear.

Regardless of where these interventions eventually settle, there can be no doubt that US farmers have been disadvantaged by government interference. This has been evidenced by immediate outcomes so there is no missing the correlation – and the associated increase in risk. China’s share of US soybean exports reached a high of 62% in 2016; following the imposition of tariffs in 2017 they fell to a low of 18% in 2018. Although exports to China rebounded in 2019 and 2020 and finally reached 55% in 2023, this was roughly the same percentage as in 2008, and well below the average of the intervening decade.8 In contrast, Brazilian exports to China surged from roughly 50% in 2008 to 70% in 2012 (helped by the massive drought in the US) and peaked at 82% in 2018, a benefit they received due to the trade war started the year before.9 On a macro level, when added to increases in cost of production that have been experienced, net farm income has fallen by almost 25% since 2022 – from a peak of $181.9 billion in 2022 to about $140 billion in 2024.10

Think risk management

For investors and farmers the picture is complex. Some of the macro trends discussed above are evident elsewhere in the agriculture investing universe; most countries are experiencing higher interest rates, stress on farm income and have seen either declines in land value or lower year-on-year increases.11 The exception, perhaps not surprisingly in view of the trends discussed above, is Brazil, which has seen a doubling in values between 2019 and 202412, with particularly strong increases in pastureland, and converged on prices in states like Illinois, but there are expectations of a slowdown.

Impact on valuation from higher rates and changes in risk profile is to be expected. As at July 8, 2025, the yield on 5-year Treasury bonds was around 3.96%; while it is always subject to numerous variables, average annual cash yields on US farmland have ranged between 2% and 5%. So even in the absence of changes in risk premia, the WACC (weighted average cost of capital) for farming and farmland assets must have increased from historic levels. The ‘traditionalist’ view is that annual capital increases from appreciation in value has resulted in a farmland total return profile of approximately 12.75% annually viewed in a 20-year context. However, over a 5-year timeframe this figure drops to 6.4%.13

Farmland remains a compelling asset class with both income and inflation-hedge characteristics but in the current environment with highly liquid global pools of capital both investors/owners and farmers need to be conscious that money is likely to flow to assets offering superior risk and return attributes. So, the question is, how can agriculture industry stakeholders best position themselves to compete for capital and generate returns in this enhanced risk environment? Some ideas:

~ Business model review: Agriculture will always have an elevated risk profile. For investors the challenge is to invest to benefit from both the defensive attributes of real assets-based investments but to obtain more robust, less volatile returns. To do this requires embracing complexity to build more resilient businesses in their portfolios. It suggests that more passive structures will need to be reviewed and, perhaps, superseded by new and more engaged offerings which can be a source of value to both the owner and the tenant;

~ Embrace risk, and manage it: Agriculture portfolios provide opportunity to deliver value to tenants through a range of services and other capabilities. These can be based on business needs that tenants may feel they are unable to address based on size, but which can be ‘spread’ over a larger base to create scale. This would in a sense co-opt the model of ag cooperatives and apply it to private portfolios. Of course, this model would only work if farmers/tenants are prepared to share their data, but as an example it is possible to envisage pooling of expected yields to deliver enhanced risk management/hedging, access to exchanges and so on that will reduce risk and, perhaps, improve profitability and creditworthiness – all of which is in the mutual interest of both tenants and their landlords. Deployment of risk management systems and development of relevant relationships with trading counterparties would likely incur some upfront cost for the landlord, but this could also be recovered in multiple ways;

~Prepare for change: Recent developments suggest new models that could substantially change the way that commodities are financed and traded. The announcement in April 2025, of the purchase of 70% of Adecoagro by Tether could very well be a harbinger of things to come and the catalyst for increased importance for stablecoins in the world of agri commodities. The market capitalization of stablecoins now exceeds $240bn, from almost a standing start in 2020,14 so there is real purchasing power that is being accumulated. At its most basic level ‘crypto’ (also known as ‘digital assets’) provides a mechanism by which payments can be made outside the traditional, US Dollar-based, financing frameworks. In the case of Adecoagro, Tether’s main business is USDT, a digital currency backed mainly by US Treasuries, so this investment could represent a first step in the fusion of digital currency and real assets. Cross-border trades could be major beneficiaries. The market for farmland could be affected, too, as use of stablecoins increases;

~Purchasing power improvement: Pooled interests can also facilitate aggregation of purchasing power to achieve better (lower) costs. Corporate landlords in particular can support their tenants by taking advantage of this opportunity while still ensuring all requirements are determined at the tenant level;

~ Best practices: Passive landlords can improve their portfolio quality and value by ensuring best practices are shared among all their tenants. Creating forums for regular exchanges of ideas, uses of new technology, sharing of operational outcomes and other items is easy to implement and creates intangible (and likely also tangible) ways of improving each tenant’s operations; and

~ Standardize processes and automate: Technology provides numerous ways to simplify core business processes, facilitate field and inventory management and allow simpler and more complete communication and reporting. Standardizing allows more consistent metrics and KPIs, better tracking and performance management and should allow owners to improve overall portfolio performance. The standard response of not wanting to tell tenants how to farm is always understandable and ‘right’ – being able to have a consistent (side-by-side) view of each portfolio position and its performance is the best way to ensure investors have measurable and meaningful data that tracks their investments and does not impinge of farmer turf.

___________________________________________________________________

May 16, 2025

Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Singapore and Switzerland

US Crop Safety Net Policy since 1975 as Margin Safety Net, Farmdoc DAILY, University of Illinois, December 9, 2022

Farm Income and Wealth Statistics – Government Payments by Program, USDA ERS February 6, 2025

Ibid

Cutting Federal Farm Subsidies’, Briefing Paper 162, by Chris Edwards (Cato Institute). August 31, 2023

Agriculture Department to Crack Down on Chinese Ownership of American Farmland, New York Times

Farmdoc DAILY, University of Illinois, February 20, 2024

Ibid.

Market Intel, American Farm Bureau, December 3, 2024

BNNBloomberg, March 18,2025 (Canadian farmland values rise nine percent, but rate of growth on a downward trend); Rabobank May 5, 2025 (Australian farm price outlook 2025: Modest land value growth expected following 2024 contraction); Farm Credit Services of America, January 7, 2025 (Farmland values stable, market shows signs of downturn)

Valor International (Agricultural land prices more than double in 5 years), January 14, 2025

About the Author:

David has been an ag investor having launched a sector specific fund in 2008 and has been an adviser to emerging growth companies and investors across the sector. He is now Sales and Growth Lead for Phlo Systems Ltd in London. Phlo offers unique solutions for commodity-based businesses including: end-to-end ERP and CTRM (commodity trading risk management), a comprehensive trade finance management platform for non-bank trade finance providers and customs clearance and compliance software and services.

Comments